Degrees Without Dividends - But AI Can Help Redefine Opportunity

The graduate premium—the idea that a university degree guarantees higher earnings and better prospects—is fading fast. In developed economies, its decline is well documented. In Africa, less so—even though it is more urgent.

The causes are not mysterious. First, scarcity has turned into surplus. Degrees once signalled rarity and access; now they are commonplace. Second, in developed economies, the original surge in higher education coincided with the expansion of the services sector, which absorbed new graduates in large numbers. That phase is over. Automation, saturation, and economic stagnation have closed that window, yet the credential pipeline continues at full throttle.

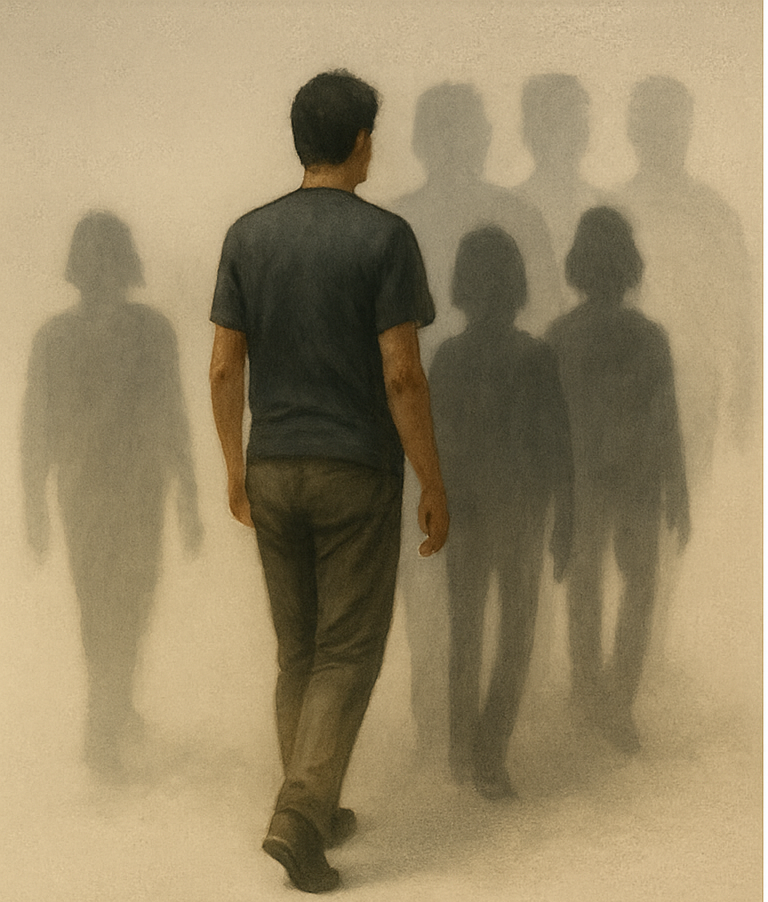

In developing economies, the surplus has emerged without the benefit of any history of good employment prospects. There, education has long been sold—by governments, donors, and institutions—as the gateway to prosperity. Families stretch finances, sell land, and make sacrifices to support their children through school and university. The students ran up the hill of education only to find nothing there at the top.

The result is a quiet crisis of misallocation. Developed economies are producing more graduates than their structures can absorb—creating downward pressure on wages, delayed life choices, and widespread frustration. The public discourse is still catching up, searching for psychological or generational explanations when the reality is structural and global. So while in Europe graduates settle for less and stay at home longer, in Africa social unrest is visible. Graduates are not a passive rural population that underpinned votes for historic leaders. They are urban, literate, and globally aware. The promise to them has not been kept—and the consequences will not be quiet.

The absence of industrialisation is at the heart of this. Without a vibrant, job-generating manufacturing base, the sheer number of young, educated people threatens to overwhelm fragile political systems. It is no longer a question of underdevelopment. It is a question of stability. Mass higher education without economic modernisation creates a population too informed to ignore their exclusion and too large to contain it peacefully.

It is urgent, therefore, to answer the question: if the degree is no longer the ticket it once was, what replaces it?

In developed economies, this is now the key policy and economic question: what will count as a premium skill for the next 25 years? Not everyone can be a coder. Leadership and soft skills are too narrow to carry a generation. The strength of university education—when it worked—was that it taught people how to navigate complexity, how to solve problems, how to make decisions under uncertainty. These were general-purpose cognitive tools, usable across every sector.

Today, those same skills are being redefined by technology. AI is changing the landscape not by replacing workers directly, but by changing what productive work looks like. The new premium may not be in any one profession. It may lie in the ability to orchestrate productivity across multiple domains, using AI as a multiplier. The graduate of tomorrow will need to master not a single discipline, but the skill of coordinating, prompting, supervising, and judging the output of multiple AI agents across tasks.

In short: the degree once allowed a person to double their effectiveness through trained thinking. AI now offers the chance to quadruple it—but only to those who know how to use it. The next premium skill may be this: how to do more, better, with AI—not as a technician, but as a strategist and orchestrator.

Maybe this is also where Africa’s story could change. The same tools that threaten jobs in the formal North could enable leaps in the informal South. AI offers not just productivity gains for existing tasks—but entirely new ways to define and deliver value. It can fill gaps left by poor infrastructure, expand access to knowledge, disintermediate inefficient systems, and spark entirely new forms of entrepreneurship. In Africa, where institutional limitations have long held back progress, AI may offer a way not just through old constraints, but around them.

The potential is real. What’s needed now is imagination, urgency, and support for the cohort that will not just use AI, but shape it—to solve problems that haven’t been solved, and invent roles that don’t yet exist. This will not come from legacy institutions or cautious reform. It will come from people who understand that AI isn’t just a tool for doing the same things faster, but a platform for doing different things altogether.

The end of the graduate premium is not the end of opportunity. But the premium is shifting—to those who can learn fast, think in systems, and turn intelligence into action, wherever they are.